My Father and the French Cemetery in Korça

"Ici réposent 640 soldats de l'Armée Française, morts pour leur patrie, 1916-1918" "Here rest the remains of 640 soldiers of the French Army fallen for their homeland", is written on the entrance gate of the "French Cemetery" in the city of Korça.

This plot of marble graves, where the care and order and human attention to every detail is immediately noticeable, has become a meaningful fragment of the common Franco-Albanian history. A piece of Albanian land, inextricably linked with the blood and flesh of France and where, for more than a century, radiates peace and meditation, respect and honour, gratitude and humility and above all learning for the future.

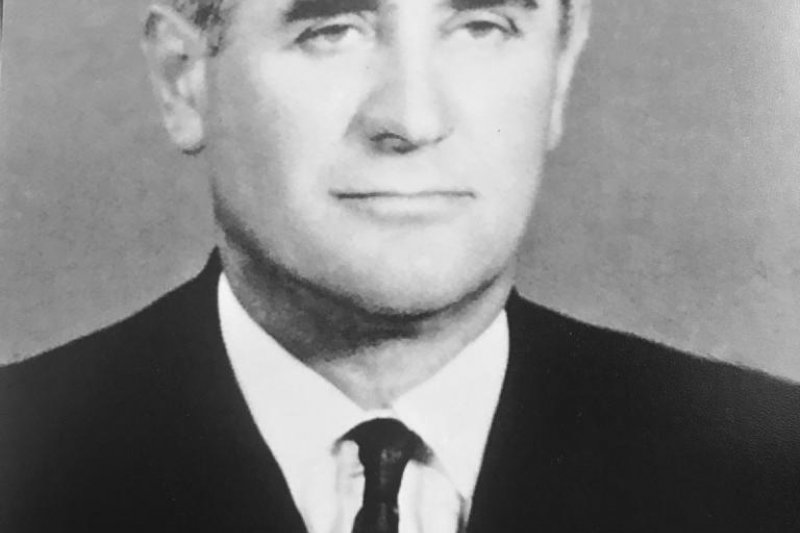

I have visited this physical piece of history since I was little, accompanied by my father. Because of his obviously deep Francophone and Francophile affiliation, from his studies at the French Lycée and later in Lyon, my father told, with all the details and undisguised emotion, the tragic story of these sons, who rest in peace away from their families and homeland, for which they gave their lives. He never forgot to emphasize that this marble cemetery is an inalienable and living monument of the history of the relations, clearly special, between the city of Korça and France.

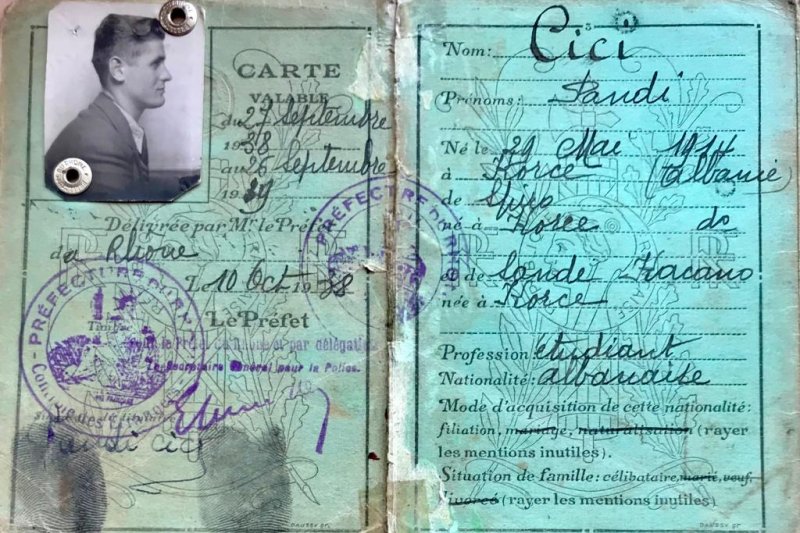

"Historians generally glorify the winners, while politicians especially use history for their own interest, but living evidence, like this cemetery, cannot be alienated, appropriated, or hidden by anyone," my father, Pandi Spiro Cici, told me when he started talking passionately about this piece of Franco-Albanian history.

This French cemetery was located on the northern outskirts of the city of Korça, in the direction towards Follorina, in front of the large park later called 'Rinia' Park. During the years of the "Great War" (La Grande Guerre) and the "Autonomous Republic" of Korça, the French began to bring here the bodies of fallen soldiers in the Balkans, as a temporary resting place. Gradually it took the form of a real cemetery. After the decision of May 20, 1920 to leave Korça, the French Military Command also prepared to withdraw the troops from this cemetery. According to my father, the pariah of that time of Kaza of Korça and the citizens themselves asked the French not to remove the bodies of their martyrs from this place. The decision to fulfill this wish was very difficult. However, due to the respect, honour and care that the city of Korça had shown to the French in general and to this cemetery in particular, during the years of Franco-Albanian coexistence, France decided to leave this cemetery of its soldiers in Korça.

The French military authorities left, leaving behind not only this sad part of their trunk, but also a "Petit Paris", with a French Lyceum and a Francophile environment, like a little patch of bleu-blanc-rouge, and the only of this type, throughout the Balkans.

Korça is the only city in the Balkans, which gave and is giving shelter and care to French soldiers who died during the First World War, my father often repeated that to me, adding that Albanians, but especially the French, should not forget this fact.

The French military forces that left Korça later took care to bring the crosses for this cemetery from the city of Thessaloniki, thus fulfilling their last service to this cemetery in a foreign, but very friendly and hospitable land.

Over the years, the space between the city and the cemetery was gradually filled. The Skenderbeu football stadium, the Children's Home and the "Petro Nini Luarasi" Pedagogical School were built together with the dormitory. Later, surprisingly, a military ward was added that had a common wall with the cemetery. That road no longer remained deserted because, beyond the cemetery, several large enterprises of the city were built, such as the car park, the geological enterprise, etc.

It turned into one of the most frequented roads of Korça, especially during the shift change hours of these enterprises. Every day, hundreds of people passed noisily, less on the cemetery sidewalk, more on the opposite one, especially in the morning and at three in the afternoon. Surprisingly, along the 30-40 meters of the length of the wall and railings of the cemetery, as if it had become an unwritten tradition, the voice was lowered and perhaps they walked slowly and without making noise. Or maybe that was my feeling. And so it really happened to me. I spent, for almost six months, every day back and forth, next to the cemetery wall, when I was working, after high school, in a company on the outskirts of Korça, and I experienced this feeling. A sense of calmness, respect and humility spread within my being. I happened to stop almost, at the time of blooming carnations, to please my eye with their beauty and enjoy the incomparable aroma, mixed with the fresh breeze coming from 'Rinia' Park. A very special place where a silent and continuous spiritual communication seemed to take place between the citizens of Korça and the souls of the killed soldiers, their memory, work and testimonies about war and peace, about death and life, about evil and the good. A dialogue that still continues today.

Maybe what happened to me happened to everyone?! I do not know. But I had and have a reason of my own, however.

I was in first grade when I learned that there was a French cemetery in my town. One beautiful, fresh day at the end of September, my father was waiting for me at the metal door of the Pedagogical school, where I started and finished elementary school. He was the director of this school for many years. He never met me at school. We used to go home at different times. He was waiting for me on his Diamant bike while I was with my friends, with whom I used to ramble home, through Rinia Park, running, climbing the Belvedere and climbing trees or sliding through the snow, during the days of winter. Although my house was not more than a hundred meters from 'Lëndina e Lotëve' or the old Radio Korça, I happened to return even after an exhausting hour or two.

My father, after greeting me, told me quietly that he was going to show me something. I knew him. He spoke quietly, sonorously, and did not like to drag on and on. He was direct and very fair. He naturally commanded authority and respect. The deep blue eyes and the peaceful expression of his face made it easier to understand his state of mind even better. Although without much pleasure, I followed him because, knowing the nature and character of my ego, I realized that it was something, if not important, unusual and interesting.

On one hand his Diamant bicycle and on the other with his hand on my head, we walked, chatting normally, the short distance between the end of the yard of the Pedagogical school and the "French Cemetery". He began to speak French to me and to go back to some lessons of "Première Année", the text-method, with which he had started French at the French Lyceum. He had started, for some time, to teach me French as well, accompanied by cartoon magazines that he had brought from France. The steps slowed as we approached the beginning of the perimeter wall and short railings of the "French Cemetery". It was the first time I came to this place. But by no means the last time. I was surprised that my father was taking me near a cemetery. To a child, this word was laced with fear and horror and ghost stories from movies, books and legends. Hesitation faded with positive surprise. The attractive aroma of carnations caressed the nose, while the eyes were delighted by the variety and care of their planting, almost everywhere. It was the end of September and normally it should have been their last days, but it didn't seem that way. Undaunted, they appeared to be at the peak of their blooming season.

To add to my curiosity, my father told me that cloves, in scientific language, are called Dianthus. In ancient Greek it means Flowers of God, from Dios-God and Anthos-Flower, he added, looking me directly in the eye.

This is a special place my son, began to speak my father. It is a historical place. It is not a cemetery like any other. In this place rest the bodies of French soldiers who died during the World War I, which caused about 20 million victims, almost half of them civilians and completely innocent. This terrible war brought a lot of misery, misfortune and pain and, moreover, by not fundamentally healing the causes of its beginning and leaving the most important issues unfinished, only 20 years later, it created the premises for the beginning of the World War II, even more terrifying than the first.

This plot of land is mixed with blood and tears, with pain, sorrow, despair, toil and suffering and much longing, here and there. Here rest the French soldiers who fell martyrs, fighting far, far away from their families and homeland. They fell for the bleu-blanc-rouge flag and fought in the hope that one day they would return to their families and loved ones to show them, once and for all, how beautiful and precious peace and love are and how terrible and unjust is war and hatred, my father said.

This cemetery, apparently not very important, is a real emblem, engraved not only in the memory of those who lived those difficult years and on the pages of chroniclers, but also in the Albanian land. Every year that passes, the foundations and roots of this emblem go even deeper in the Albanian land and, to my question, why they haven't buried them in France, he calmly but convincingly answered because even here they are equally respected and honoured as in their country. Their rest here is a sign, evidence and proof of the French Korça and its francophoneness and francophilia. Things are connected, my son, he continued. This plot was donated to France by the Korca citizens, to respect these sons of mothers who gave their lives away from their families, mothers, wives and children that they loved so much. Giving this land to France, at that time, is at the same time a gesture of gratitude towards France's vital role in the proclamation and preservation of the "Autonomous Republic of Korça" in difficult times for this city and all of Albania, seems to have concluded my story his, that day.

He turned the Diamant bike in the direction we came from and calmly started walking, knowing that I was following him by his side, surprised, but also happy, as if he had trusted me with a big secret, after a difficult ordeal.

But the secret was not complete. Not long after, I was alone with my father, in the warm room of the house, sitting at the middle table, to continue my French lesson. Suddenly he closed the book and asked me if I remembered the story of the "French Cemetery" and, without waiting for my answer, began his story, even more fascinating.

On the 20th anniversary of the "Armistice of the Great War", as the First World War was called, I was a student in Lyon, my father said. That morning of November 11, 1938, the professor of the history of the Middle Ages, at the same time the Dean of the Faculty of Letters of the University of Lyon, Professor Arthur Kleinclausz, enters the auditorium and reminds us of this important day in the history of the world and that of France. He spoke at length about the catastrophic, human, economic, social, national and international consequences of WWI, but he focused especially on the danger of the ghosts of the unfinished war, as he called it, which had begun to move in the gloomy sky of Europe.

As my father said, Professor Kleinclausz, next, expressed his dissatisfaction with the Munich Agreement, just signed (September 30, 1938) between Hitler, Mussolini, Chamberlain and Daladier, and was very critical of the French Prime Minister, who had become part of this signing, at a time when the extermination strategy of the Jews had begun in Germany after the violation of the Treaty of Versailles and Mussolini's Italy had left the League of Nations.

After Dean Kleinclausz had asked the students of the course to observe a minute of silence, in respect of the fallen of France during WWI, he surprised everyone by adding that a cemetery of French soldiers is located in a small country in Europe called Albania. Among you is a student from this country, he added to everyone's surprise, mentioning my father's name and asking him to stand up. Those soldiers buried there could not return to their homes, but they are as respected, honoured and valued as French soldiers on French soil. We must be grateful to this small country, for this great gesture, Professor Kleinclausz concluded the lecture, that marked anniversary of world history, making me feel very, very proud of the country and my beloved city, concluded my father the confession of his secret.

This exciting story completed the secret of my father and his memories with this cemetery that he could not keep to himself. It increased my desire and drive to find out more about these cemeteries and their painful history.

I don't know if my father managed, while he was alive, to bring a bouquet of flowers in honour of this "battalion" who fell for the French flag, but every time I go there, it's me and my father, my father and I, undivided, in honour of this historical monument, and I feel a lot of emotions and pride.

So much emotion for the painful story of every soldier lying there and the unspeakable longing for them and their families.

Pride for my father, for my family and background, for my city.

Pride for the care, respect, attention and citizenship shown, continuously, to not leave these soldiers alone and for the privileged relationship that Korça has with France, the French language, culture, literature and civilization, of which it has become a part also "le Petit Paris".

Also this November 11, me and my father, my father and I, inseparable, will go to lay flowers in this symbolic cemetery.

Then I will go to my father to talk to him, although I know that he told me the most beautiful stories while he was alive.