Albania-Greece Maritime Border, A Short 75-year History

It was October 22, 1946 when a British military ship crashed into a mine near Saranda and then the other British ship that went to help had the same misfortune. The balance was tragic: 44 dead and as many wounded.

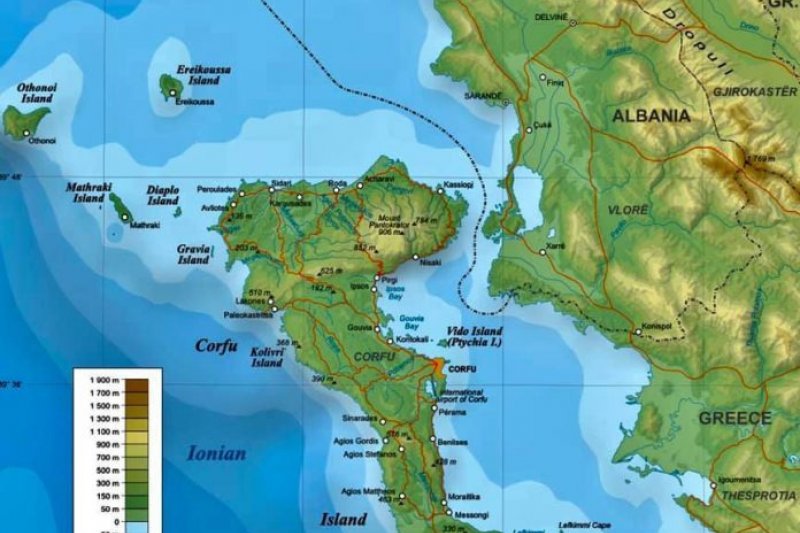

Three weeks later the British fleet took a unilateral mine-clearing action for about three nautical miles along the passage from Saranda Bay down the Corfu Channel. The Albanian government protested, saying that its sovereignty in its waters was being violated, and the British government, an ally of the Greek government, said that they are international transit waters and we are exercising the right of cleaning and reclamation in this canal.

The British government and its allies accused communist Tirana of deliberately planting those mines, while Enver Hoxha's government said it did not possess them and could not place them.

At the UN, Albania was defended by the Soviet Union, but again this case was left to be tried by the International Court of Justice in The Hague and this would be the first case that this newly established court would try.

Three years later, in 1949, it took two decisions: condemning Albania for setting up a naval minefield despite being in its maritime waters and condemning Great Britain for violating Albania's territorial sovereignty by carrying out a unilateral military sweeping operation without permission of the Albanian government.

The British claimed that it was not Albanian waters as the border had to be measured by the lighthouse of Peristeri, a piece of stone in the sea between Corfu and Saranda, which the Greeks call an island. But the court ruled otherwise.

63 years later in a completely different geopolitical context Greece demands the division and delimitation of waters with Albania. As it now demanded more, due to the submarine energy resources opposite Saranda west of Himara and north of Corfu, Greece claimed the exact opposite of what it wanted in 1946 and the decision of the Hague Tribunal.

Knowing that the decision of the International Court of Justice is uncontested, Greece pursued a ploy, a bilateral delimitation agreement with Albania, devaluing the recognition of Albania's territorial sovereignty in 1949. The then Prime Minister Berisha decided to embark on this adventure and signed an agreement, very harmful for Albania. The Albanian government obtained visa liberalization, but lost maritime territory, and Greece, in addition to the sea, managed to sign a bilateral agreement on the principle of delimitation with twelve nautical miles, which was of great interest for the southern Mediterranean opposite Turkey. The opposition of the time with the lawyers who would later become ministers, Damian Gjiknuri, Ditmiri Bushati and Saimir Tahiri took it to the Constitutional Court.

The court not only overturned the agreement of the Berisha government, but gave a unique decision in the history of Albanian jurisprudence and not only, going into detail describing the delimitation of the sea border.

A few years later Greece repeats its old trick again. Greece, this country that has 5,500 islands practically an archipelago like Indonesia, seeks to get the last stone in the sea with Albania.

Of course it does not need the sea but what is under the sea. The trick this time is more sophisticated, in the ministerial offices are those who were the former opposition and who won in the Constitutional Court.

Greece gives Albania the sea opposite Himara and Dhermi where there are no energy resources and takes the share of energy resources, under of what is known as the Exclusive Economic Zone.

Foreign Minister Bushati and the Prime Minister wanted to hurry to sign this agreement. Yet they found themselves powerless in the face of the Stoic resistance of the President, who calmly and argumentatively confronted them with the Constitutional Court decision they themselves had made, the historic practice of delimiting maritime waters with Italy that had lasted eight years, and the historic political and legal relations between Greece and Albania.

History returns to the political table again, at the height of an economic crisis in Albania, of Kosovo's political weakness, which is not only required to hand over political leadership to The Hague, but also to change borders. It is true that the devil hides in details and the Greeks know full well that details make the difference, so they insist.

But today we have a decision of the Constitutional Court and a head of state who knows very well the importance of that decision, not to include Albania in the vortex of a Greek-Turkish conflict, because this "short" 75-year history between Albania and Greece is enough for us.